Work is progressing on the Starr Park site. The concrete slab is in place, timber decking is next #historic #shubiecanal #dartmouth

Sealing of the Time Capsule

At the end of their grade 12 year, students from Dartmouth High have added their mark to the 19th-century Flume House/Turbine Chamber being constructed at its original location in downtown Dartmouth. This group of students prepared a time capsule and placed it in a granite block vault located inside the replica Flume House. This capsule will remain closed for 50 years at which time it will be opened by the Dartmouthians of that day. As part of the time capsule sealing ceremony, held on June 12, student Ethan Gysbertsen read a letter he wrote to the students of the future. That letter is below.

Ethan Gysbertsen, Grade 12 Global Geography student, reading his letter at the event.

Canada 200

No introduction seems exactly appropriate, this message is one that will be heard half a century into the future on the year of Canada’s 200th anniversary; standing here on the 150th anniversary, it’s hard to even begin to think how things will have changed, but to those listening it must seem like it couldn’t have gone any other way, and we can only hope that you don’t wish it had.

Our language does not serve us well in addressing people and places that do not yet exist to receive our messages, but by burying this time capsule we are attempting to do just that in the hopes that we will not be forgotten or laid aside by the march of time; and so this is our address to the future.

A lot of you here today may not remember what has effectively been the first fifth of the twenty first century, and you probably have no reason to even consider what went on during this time; you have your own world to experience and live in, but from here, we hope that maybe some of the things we did right have helped to make your world what it is; in your culture, in your art, in your technology, and in the people that inhabit it.

We were not perfect, we were fallible, and human, but we hope that you were smarter, and stronger than us, and did things that we did not have the will or the vision to achieve; that you took up the challenges we have today and were able to fulfill the promises for change that we have made, despite the shortsightedness that we have practiced.

For all the talk of the future that we make, we have little but wild conjecture; and for all the talk of change, the world rarely changes in the big ways that we imagine. History has shown that changes are slow and small, but inevitable, and while they might change the small ways we live our lives; how we communicate, who we talk about, the amount of money in your pocket, the way we think about the world, the point is we have always cared about and done these things, and it is doubtful fifty years is going to make a dent in these practices.

But imagination is one of our best qualities as a species, it drives us to make the decisions we do in the hopes of a better world; so from fifty years ago, here are some of the things we hope to change and have started to see changing in the meantime.

An Ebola vaccine has been developed that so far had demonstrated a 100% success rate, world hunger is the lowest it’s been in 25 years, the ice bucket challenge has allowed us to isolate the gene that causes ALS, the giant panda and the manatee have been removed from the endangered species list, six people have been rendered HIV negative by modern medicine, projects have begun that plan to remove massive amounts of plastic from the world's oceans, gravitational waves have been discovered, and work has begun on the world's first commercial fusion reactor.

We have promised to drive our infrastructure towards renewable energy, we strive to end conflict, and we seek betterment for the lives of every citizen, no conditions attached. These, and similar sentiments, are the real legacies that we will be remembered for; these are the ideals that will influence the world fifty years to come, and it is the precedence and examples that all of you here with me now set in that time that will affect the lives of those who live in the world we will leave behind.

To all of you listening, where you are, and how you live is what we leave behind for you, not these artifacts or my words; it was our responsibility to lay down the groundwork for the times to come, and as you live the realization of that world, hear now from its humble beginnings, the promise of its construction. To everyone here with me today, let's get to work, we've got a lot to live up to.

Ethan Gysbertsen

Grade 12 Global Geography student

Bill McIntyre, SCC Chair, speaking to the students at the event.

Plaque and time capsule on display at the event.

Dartmouth High School Global Geography students with their teacher (L) Terry Sampson.

Why did the Scottish vessel Corsair bring Irish canal workers?

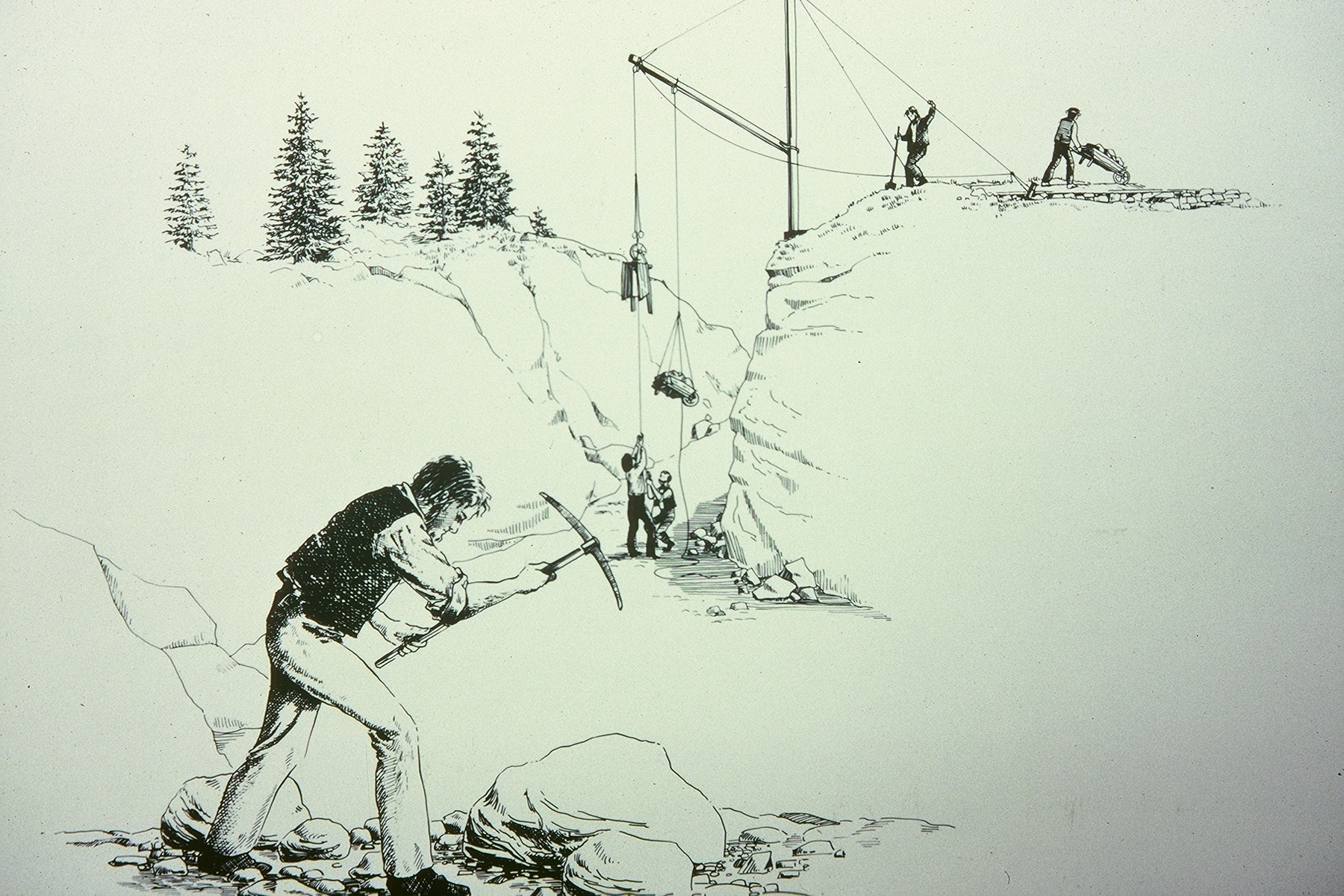

One of the most interesting features of Shubie Park is the "Deep Cut". Which is the waterway between the bridge near the Camp Ground and Lake Charles. Below is the Engineer’s report which refers to the work going on in the area on May 1827.

“…..one hundred and fifty men have been employed upon the deep cutting….The present deficiency of granite workers will be made up as soon as a vessel chartered for the express purpose can return from Scotland, in the meantime such hands as can be procured are employed and liberally rewarded for their labor.”

The vessel referred to in this quote is the Corsair which brought workers from Scotland to Dartmouth to work on the Shubenacadie Canal. One of the puzzling features of this report is that while the vessel came from Scotland most of the workers on board were Irish and not Scottish. For a long time this inconsistency was a bit of a puzzle – until several people connected with the Shubenacadie Canal attended a Conference in Scotland and discovered that just prior to the 1827 crossing of the Corsair there had been a canal workers strike in Scotland. In order to complete one or two key projects the striking workers were replaced by a crew from Ireland. Work on these projects terminated at just about the time the Corsair left for Nova Scotia. “Bingo” mystery solved – and now it is clear why the folks on the Corsair were mainly Irish. As we have indicated before there are still a number of descendants of these workers living in this area.

-Bernie Hart

What's inside of the Flume House?

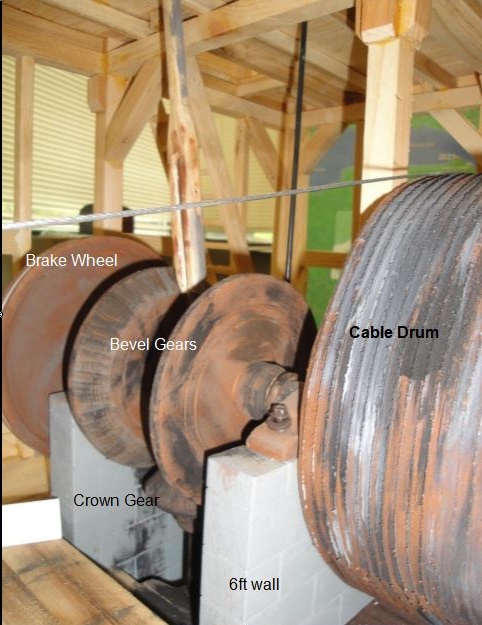

Now that we have the Flume House, we are focusing on building the components found inside. The cable drum, seen below, is nearing completion and will be installed on site soon.

Seen above is one side of the cable drum that is being constructed by Martin Developments.

Engineering Features of the Flume House Machinery

When the Marine Railway was in operation it was water powered. The water was brought into the Flume House and then it was discharged through the reaction turbine (first image), rotating a vertical shaft that drove the crown and bevel gears and, through a third gear, drove the 12 foot diameter cable drum (second image). The drum hauled a 2 inch diameter cable attached to the boat cradle. The boat cradle and its load were lifted from Halifax Harbour to Sullivan’s Pond along the Marine Railway.

Model of a reaction turbine

Model of the gears and cable drum

In this photo from the Morris Canal you can see the cable that pulls the boat cradle.